annu daftuar

Department of Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Graduate Student

Guiliano Fellow, Fall 2020

"Global Fertility Markets: Regulation and Reproductive Justice"

My dissertation, “Global Fertility Markets: Regulation and Reproductive Justice” examines the evolution of commercial surrogacy industry in India after the Indian government closed it borders transnational surrogacy in late 2015, prohibiting foreigners to pursue surrogacy services in country. Specifically, I interrogate the Indian government’s claim that banning surrogacy would protect surrogates from exploitation, and examine where the surrogates actually benefitted from the ban to investigate whether blanket bans are an effective way to address the challenges of a globalized surrogacy market.

My research captures implications of the 2015 transnational surrogacy ban on key stakeholders in the Indian surrogacy industry: the fertility clinics, the infertile individuals/couples, and most importantly, the surrogates who are most marginalized in surrogacy arrangements, to understand the different stakes of each. It also interrogates how infertility and Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ARTs, technologies that assist in conception) are framed in the Indian state policies and the Indian feminist movement. Specifically, I ask: How is ARTs and surrogacy framed/defined in these two sites? Do the current policies and public discourse around ARTs and surrogacy in India mark a break from its long and aggressive history of population control policies? How does the Indian government resolve this paradox of controlling population on the one hand, and passing laws on infertility management and ARTs on the other? In the process, what new cultural definitions of womanhood/motherhood and family are constructed and how are they linked to nationalism? Additionally, I examine the ways in which the Indian feminist movement discusses and addresses the issue of procreative technologies, and how do local/nationalist feminist movements complicate larger global feminist movements on assisted reproductive technologies.

Initial Findings:

My research demonstrates that the 2015 transnational surrogacy ban neither deterred

growth of the commercial surrogacy businesses for Indian fertility clinics both within

India and transnationally, nor did it reduce vulnerabilities of the surrogates (lest

‘save’ them from exploitation). The fertility clinics and stand-alone surrogacy agencies

in India now offer surrogacy services to Indian citizens instead of foreign nationals,

and collaborated with fertility clinics in different countries like Georgia (where

surrogacy is legal) and Kenya (where no surrogacy law exist) among others to continue

offering surrogacy services to foreigners and Indians with foreign passports and

expand their fertility businesses globally. The project reveals a complex dynamic

of stratified reproduction (Ginsburg and Rapp 1995) along the lines of class, caste,

religion, and sexuality in the domestic surrogacy industry in India. I contend that

these categories of structural  difference and inequalities shape both accessibility of surrogacy services for the

infertile individuals/couples, as well as vulnerabilities of the surrogates. Additionally,

the research reveals that the feminist movement within India is also divided on the

issue of ARTs and its regulation. While some favor its regulation through legalization, others demand complete ban of commercial and altruistic surrogacy services citing a case of forced surrogacy in South India.

difference and inequalities shape both accessibility of surrogacy services for the

infertile individuals/couples, as well as vulnerabilities of the surrogates. Additionally,

the research reveals that the feminist movement within India is also divided on the

issue of ARTs and its regulation. While some favor its regulation through legalization, others demand complete ban of commercial and altruistic surrogacy services citing a case of forced surrogacy in South India.

Screenshot of a surrogacy agency website, headquartered in India and offering surrogacy

services globally. June 2021. Screenshot taken by author.

Screenshot of a surrogacy agency website, headquartered in India and offering surrogacy

services globally. June 2021. Screenshot taken by author.

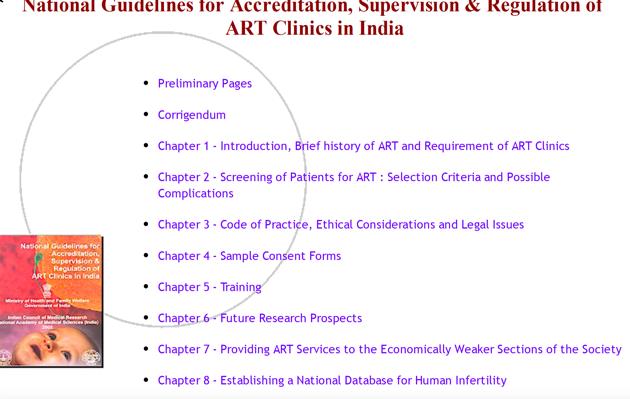

Screenshot of ART Regulation Bill 2005, retrieved from Digital Indian Parliament Library,

New Delhi, India. June 2021.

Screenshot of ART Regulation Bill 2005, retrieved from Digital Indian Parliament Library,

New Delhi, India. June 2021.

Methods:

My research was conducted in New Delhi and Vishakhapatnam in India through March-September 2021 (Spring and Summer 2021). It consisted of conducting digital archival research and in-person/virtual interviews with interlocuters such as fertility specialists including surrogate agents, infertile individuals, surrogates, feminist activists, as well as journalists, lawyers and academic scholars working on the issue of women’s reproductive rights (Note: In-person interviews were conducted only when it became more permissible to conduct them under COVID-19).

My initial research methodology of ethnography at a fertility clinic in New Delhi (with in-person interviews and participant observation) had to be changed due to COVID-19 pandemic. In order to navigate the methodological challenges presented by the pandemic, I employed feminist geographer Nancy Heimstra’s concept of ‘feminist periscoping’, which is a useful approach to study difficult-to access sites/subjects/processes. Drawing on this feminist methodology, I assembled a variety of lenses (different methods of data collection) to be able to see different aspects of the surrogacy processes even as my ethnographic research agenda of in-person interviews and participant observation were compromised by the pandemic. Most of my research was done virtually, which included virtual ethnography conducted via Zoom and content analysis conducted on digital platforms such as websites, films/documentaries, and social media such as Instagram, WhatsApp and YouTube. I also relied on documents made available on the digital library archives of the Indian Parliament and feminist organizations (due to COVID-19) to continue conducting my archival research. This methodology allowed me to focus less on one individual method and more on working with what was made available to me in the process of the conducting research. Rather than abandoning a rather difficult to access research, periscoping allowed me access to partial views of the surrogacy phenomenon which when put together revealed a more complex picture of the surrogacy industry demonstrating how inequitable power relations and structures shaped oppressive practices in the domestic surrogacy industry in India.

Data Analysis:

My data analysis consisted of tracking continuities and changes in the Indian surrogacy industry in the aftermath of the transnational surrogacy ban, and identify codes which were not identified by previous feminist scholars in their analysis of surrogacy arrangements in India. In addition, I analyze social media usage by following who posts on issues like infertility and ARTs on social media, what trends emerge and who engages with such content. I also kept a research journal to document my observations during interviews and the process of research which inform my analyses.

Contributions to scholarly work and policy making, and student learning

My project adds to ongoing debates on effective national and international policy-making for regulating surrogacy markets. It also contributes to existing scholarship and praxis on transnational feminist reproductive justice in the twenty first century. Early feminist activist-scholars have described the transnational surrogacy industry in the Global South, in which rich foreigners from the Global North traveled to India to hire reproductive services of poor women, as a clear case of stratified reproduction (Colen 1995) where bodies of women of color were utilized to produce white, middle class, heteronormative families (Pande 2014, Rudrappa 2015, Deomampo 2016, Schurr 2019). My research further complicates this knowledge by demonstrating the ways in which stratified reproduction works in the domestic surrogacy market in India, thereby pushing for a more nuanced understanding of the ways in which global and local fertility markets work.

With my dissertation, I am also addressing serious gaps in anthropological research on the uneven spread of ARTs in the Global South (Bhardwaj 2015). I build on Black feminist scholar Patricia Hill Collin’s notion of concept of ‘fragmentation of black body’ (1990) and the notion of reproductive justice (Roberts 1998; Davis 2003) which provide useful analytical tools to understand and theorize the surrogacy industry. Further, my research generates knowledge on the relationship between feminism and the state on the issue of ARTs in India which has not been documented yet, given the predominance of population control rhetoric in postcolonial India.

In terms of student learning, I would like to point out that conducting research during the pandemic was extremely challenging, and yet the most unique experience for me as a researcher. I had to rethink my original methodology and be creative with my methods to continue working on my research and not give up. One of my dissertation chapters focus exclusively on methodology and I aim to publish an article about the challenges of conducting research during the pandemic.

The Guiliano Global Fellowship Program offers students the opportunity to carry out

research, creative expression and cultural activities for personal development through

traveling outside of their comfort zone.

GRADUATE STUDENT APPLICATION INFORMATION

UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT APPLICATION INFORMATION

Application Deadlines:

Fall deadline: October 1 (Projects will take place during the Winter Session or spring semester)

Spring deadline: March 1 (Projects will take place during the Summer Session or fall semester)

Please submit any questions here.